WisniaLang: Compiler Project

Can we produce small and fast binaries at the same time?

Oct 17, 2022

c++

elf

compiler

llvm

rust

CONTENTS

Introduction

For the past 3 years, I have been working on the

Architecture

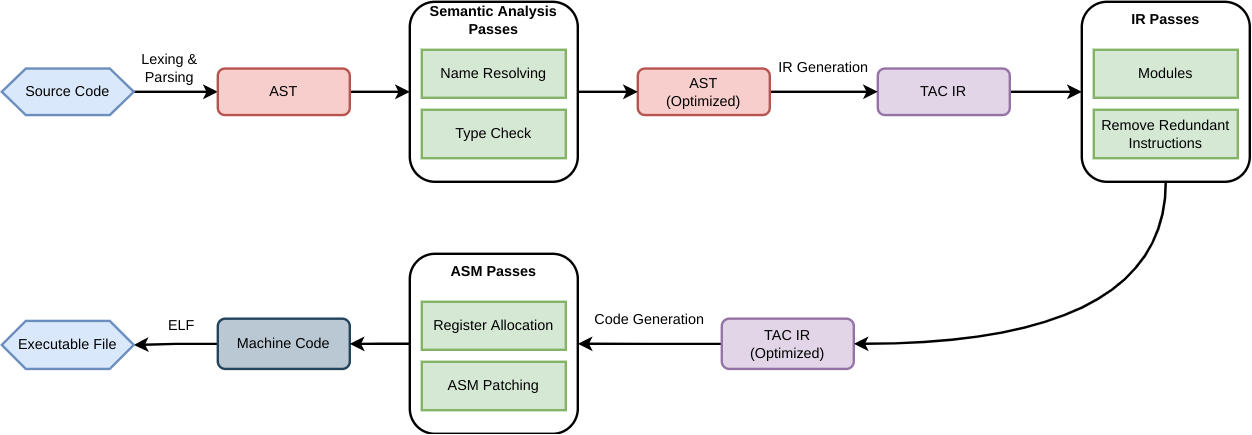

My compiler’s architecture is divided into several main phases that work together to complete this translation. These phases include lexical analysis, which breaks the source code down into smaller pieces called tokens; syntactic analysis, which builds a representation of the structure of the source code called an abstract syntax tree (AST); semantic analysis, which checks the AST for semantic errors while traversing the tree; intermediate representation (IR), which represents the code in a lower-level form close to the target architecture; code generation, which allocates registers and generates machine code from the said IRs; and, lastly, packing the resulting machine code into an executable program in ELF format.

Programming languages and LLVM

Before going further, let me get straight to the point:

- Writing compilers is easy

- Optimizing the machine code is hard

- Supporting arbitrary architectures / operating systems is hard

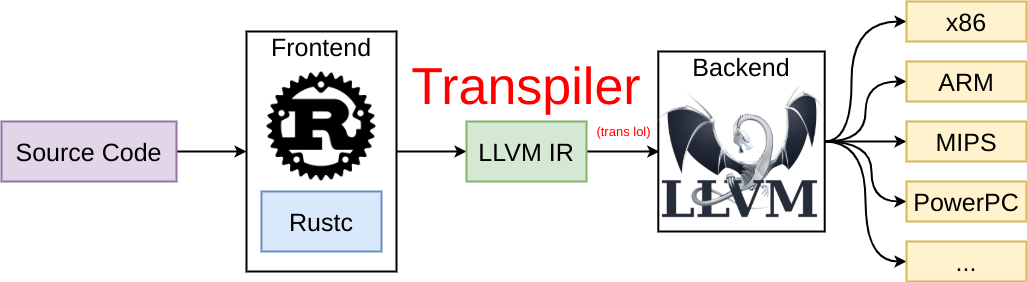

This is where LLVM comes in handy. LLVM uses an intermediate representation language, which is kind of similar to assembly, but with a few higher level constructs. LLVM is good at optimizing this IR language, as well as compiling into different architecture and binary formats. So as a language author using LLVM, I’m really writing a transpiler from my language to LLVM IR, and letting the LLVM compiler do the hard work.

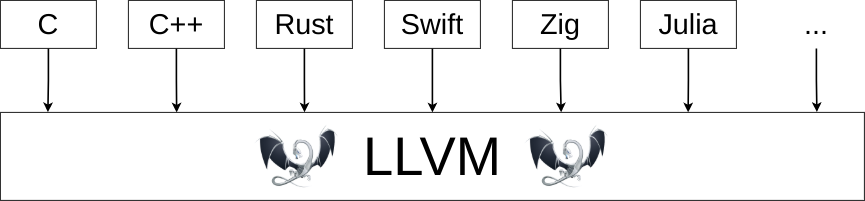

You talk about LLVM so much, why’s that? Let me begin with this illustration:

I’m not sure if it’s a positive thing, but the LLVM project has achieved such widespread adoption that it’s almost reached a monopoly status, much like the Chromium project, for instance. Apart from Google Chrome, numerous other browsers are built upon the Chromium codebase. From Electron web apps to Arc, Microsoft Edge, Opera, Vivaldi, Brave, and beyond, the list just goes on. Firefox and Safari are perhaps the only web browsers that stand out from this copy-paste crowd.

I just wanted to point out that while 99.9% of compiler developers opt for LLVM, the remaining few explore alternative compiler backends like

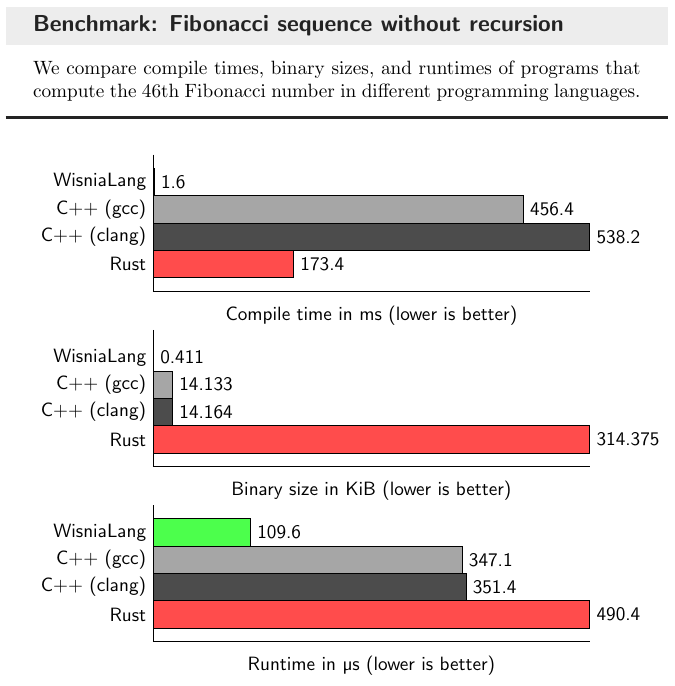

Benchmark No. 1: Fibonacci sequence

To benchmark different compilers, I chose the Fibonacci sequence without recursion problem and computed the 46th Fibonacci number with each compiler under test. This number was chosen because it conveniently fits within 32 bits. Compile-time and runtime benchmarks were performed using the strip to remove debug symbols from binaries and wc to display byte counts for each binary file.

WisniaLang benchmark

1fn fibonacci(n: int) -> int {

2 if (n <= 1) {

3 return n;

4 }

5 int prev = 0;

6 int current = 1;

7 for (int i = 2; i <= n; i = i + 1) {

8 int next = prev + current;

9 prev = current;

10 current = next;

11 }

12 return current;

13}

14

15fn main() {

16 print(fibonacci(46));

17}

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 1000 --warmup 10 --shell=none './wisnia fibonacci.wsn'

2Benchmark 1: ./wisnia fibonacci.wsn

3 Time (mean ± σ): 1.6 ms ± 0.3 ms [User: 0.8 ms, System: 0.5 ms]

4 Range (min … max): 1.3 ms … 8.7 ms 1000 runs

Runtime

1hyperfine --runs 1000 --warmup 10 --shell=none './a.out'

2Benchmark 1: ./a.out

3 Time (mean ± σ): 109.6 µs ± 36.8 µs [User: 58.2 µs, System: 4.7 µs]

4 Range (min … max): 84.0 µs … 736.3 µs 1000 runs

Binary size

1wc -c a.out

2421 a.out

C++ (gcc) benchmark

1#include <iostream>

2

3constexpr auto fibonacci(u_int32_t n) {

4 if (n <= 1) {

5 return n;

6 }

7 u_int32_t prev = 0, current = 1;

8 for (size_t i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

9 u_int32_t next = prev + current;

10 prev = current;

11 current = next;

12 }

13 return current;

14}

15

16int main() {

17 std::printf("%d", fibonacci(46));

18}

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 100 --warmup 10 --shell=none 'g++ -std=c++23 -O3 fibonacci.cpp'

2Benchmark 1: g++ -std=c++23 -O3 fibonacci.cpp

3 Time (mean ± σ): 456.4 ms ± 4.5 ms [User: 415.8 ms, System: 35.2 ms]

4 Range (min … max): 448.9 ms … 472.1 ms 100 runs

Runtime

1hyperfine --runs 1000 --warmup 10 --shell=none './a.out'

2Benchmark 1: ./a.out

3 Time (mean ± σ): 347.1 µs ± 62.8 µs [User: 206.4 µs, System: 67.2 µs]

4 Range (min … max): 271.9 µs … 926.4 µs 1000 runs

Binary size

1strip a.out

2wc -c a.out

314472 a.out

C++ (clang) benchmark

Same program as before, just different compiler.

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 100 --warmup 10 --shell=none 'clang++ -std=c++2b -O3 fibonacci.cpp'

2Benchmark 1: clang++ -std=c++2b -O3 fibonacci.cpp

3 Time (mean ± σ): 538.2 ms ± 16.9 ms [User: 481.7 ms, System: 45.7 ms]

4 Range (min … max): 524.3 ms … 657.9 ms 100 runs

Runtime

1hyperfine --runs 1000 --warmup 10 --shell=none './a.out'

2Benchmark 1: ./a.out

3 Time (mean ± σ): 351.4 µs ± 67.7 µs [User: 203.2 µs, System: 72.2 µs]

4 Range (min … max): 267.1 µs … 984.8 µs 1000 runs

Binary size

1strip a.out

2wc -c a.out

314504 a.out

Rust benchmark

1fn fibonacci(n: u32) -> u32 {

2 if n <= 1 {

3 return n;

4 }

5 let (mut prev, mut current) = (0, 1);

6 for _ in 2..=n {

7 let next = prev + current;

8 prev = current;

9 current = next;

10 }

11 current

12}

13

14fn main() {

15 println!("{}", fibonacci(46));

16}

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 100 --warmup 10 --shell=none 'rustc -C opt-level=3 fibonacci.rs'

2Benchmark 1: rustc -C opt-level=3 fibonacci.rs

3 Time (mean ± σ): 173.4 ms ± 3.0 ms [User: 130.5 ms, System: 51.2 ms]

4 Range (min … max): 168.6 ms … 183.8 ms 100 runs

Runtime

1hyperfine --runs 1000 --warmup 10 --shell=none './fibonacci'

2Benchmark 1: ./fibonacci

3 Time (mean ± σ): 490.4 µs ± 82.8 µs [User: 264.9 µs, System: 129.3 µs]

4 Range (min … max): 375.1 µs … 1092.6 µs 1000 runs

Binary size

1strip fibonacci

2wc -c fibonacci

3321920 fibonacci

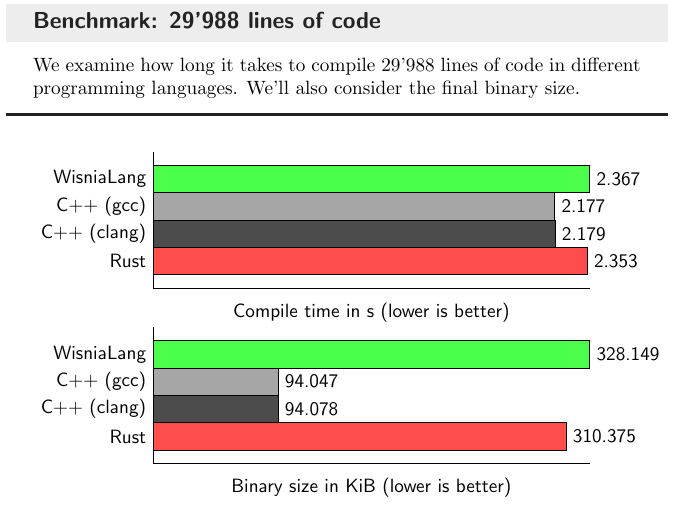

Benchmark No. 2: 29'988 lines of code

I wrote a calculate_1997, such as calculate_1, calculate_2, and calculate_1999, for over 2000 times:

1...

2void calculate_1997() {

3 int i = 0;

4 int a = 0;

5 int b = 0;

6 while (b < 1997) {

7 a = a + b + i;

8 b = a - b - i;

9 int c = a + b;

10 int d = a + b + c;

11 int e = a + b + c + d;

12 int f = a + b + c + d + e;

13 i = f - e - d - c + 1;

14 }

15}

16...

17int main() {

18 ...

19 calculate_1997();

20 ...

21}

You can run this script with python main.py --wisnia --cpp --rust 2000.

WisniaLang benchmark

The program can be found at

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 20 --warmup 1 --shell=none './wisnia calculate.wsn'

2Benchmark 1: ./wisnia calculate.wsn

3 Time (mean ± σ): 2.367 s ± 0.054 s [User: 2.328 s, System: 0.036 s]

4 Range (min … max): 2.282 s … 2.466 s 20 runs

Binary size

1wc -c a.out

2336025 a.out

C++ (gcc) benchmark

The program can be found at

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 20 --warmup 1 --shell=none 'g++ -std=c++23 -O3 calculate.cpp'

2Benchmark 1: g++ -std=c++23 -O3 calculate.cpp

3 Time (mean ± σ): 2.177 s ± 0.009 s [User: 2.110 s, System: 0.064 s]

4 Range (min … max): 2.156 s … 2.193 s 20 runs

Binary size

1strip a.out

2wc -c a.out

396304 a.out

C++ (clang) benchmark

Same program as before, just different compiler.

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 20 --warmup 1 --shell=none 'clang++ -std=c++2b -O3 calculate.cpp'

2Benchmark 1: clang++ -std=c++2b -O3 calculate.cpp

3 Time (mean ± σ): 2.179 s ± 0.025 s [User: 2.125 s, System: 0.048 s]

4 Range (min … max): 2.156 s … 2.252 s 20 runs

Binary size

1strip a.out

2wc -c a.out

396336 a.out

Rust benchmark

The program can be found at

Compile time

1hyperfine --runs 20 --warmup 1 --shell=none 'rustc -C opt-level=3 calculate.rs'

2Benchmark 1: rustc -C opt-level=3 calculate.rs

3 Time (mean ± σ): 2.353 s ± 0.027 s [User: 2.268 s, System: 0.095 s]

4 Range (min … max): 2.324 s … 2.436 s 20 runs

Binary size

1strip calculate

2wc -c calculate

3317824 calculate

Results

Combining mean compile time, runtime, and binary sizes from benchmark results, we obtain the following graphs.

The runtime range for WisniaLang was from 84.0 µs to 736.3 µs over 1000 program runs, indicating ambiguous results due to benchmarking a 17-line program that executes 3 lines of code 45 times. However, this does demonstrate the speed at which we can compile small programs. In the future, I plan to report on the recursive Fibonacci sequence.

WisniaLang generates code as fast as established compilers, but this may be because it doesn’t perform many static code analysis or optimization steps. This has resulted in my binary being quite large. In contrast, C++ optimizes out redundant code, simplifying the while loop to use at most three variables. This is the while loop in question:

1while (b < 1997) {

2 a = a + b + i;

3 b = a - b - i;

4 int c = a + b;

5 int d = a + b + c;

6 int e = a + b + c + d;

7 int f = a + b + c + d + e;

8 i = f - e - d - c + 1;

9}

What I mean is that C++ likely optimized the code to use only three variables – a, b, and i – by substituting the values of c, d, e, and f directly, thereby reducing redundancy. This is something I’ll fix in the future releases of WisniaLang.

Summary

- If compilation speed and binary size are important, dropping the LLVM toolchain can have a positive impact

- However, doing so means missing out on LLVM optimizations as well as support for arbitrary OSes and architectures